WEbuilding: Supporting communities through sustainable architecture

Life is filled with unexpected synergies. A few weeks ago I came across a story of architect Diébédo Francis Kéré and a school he built in Burkina Faso. I was drawn to his work not only for its beauty, but also the purpose it served. Hailing from South Africa, I’ve always been confronted with and troubled by the poor states of schools across our continent. I felt inspired by his pursuits and thought, I’d like to interview someone like him one day. Two days later I found a message in my inbox. It wasn’t from Kéré off course, but indeed another Berlin based architecture practice – an NGO in fact – called WEbuilding.

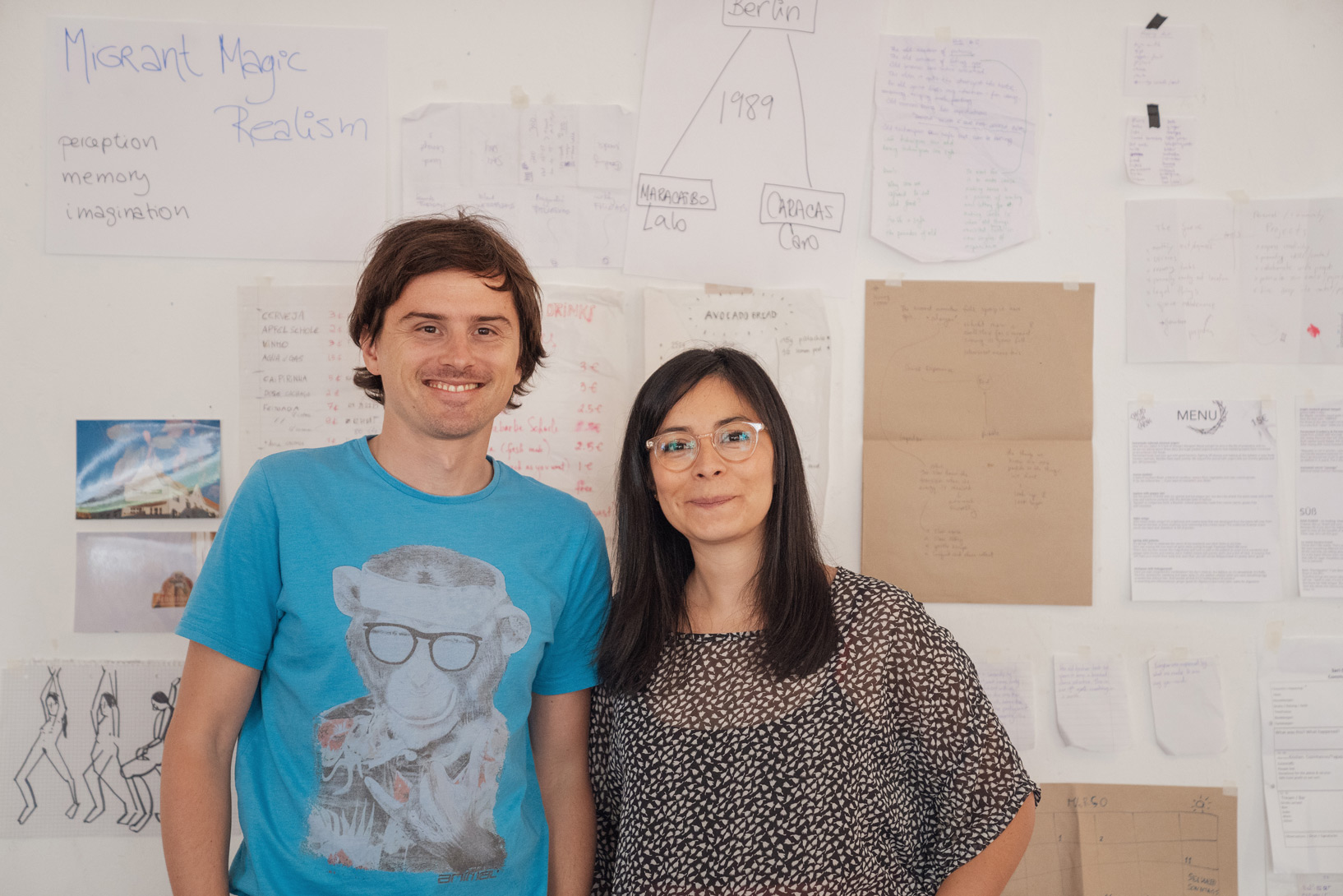

Together with their team of volunteers, the WE Building founders Laura Gómez Agudelo and Ivan Rališ, have a surprisingly similar objective; that is to build schools in impoverished communities and doing it through sustainable practices. They invited me to spend a morning at the vibrant Sari-Sari space they share with Nowhere Kitchen in Neukölln, to learn more about their work and to talk about the beautiful school they just finished in Ghana. This is their story.

Tell is a little about WEbuilding and how it all started.

Laura: “While I was at the university I discovered one can actually practice architecture in an NGO environment and help people in need. I was fascinated by the idea and as soon as I graduated I left to Ghana, where I worked at a small NGO doing the site management for the construction of a youth center.”

“A few years after, while already living in Berlin, I got in contact with that same NGO and they told me that they bought a plot, and that the community was planning to build a school.”

“We initially got involved only to design the architecture project, but very soon we figured we could try to find financing in order to build it. That required us to register an official non profit in Germany to be allowed to apply for any and that’s how WEbuilding was born.”

What is the drive behind the NGO, why do you do it and what keeps you going?

Laura: “I have no other option. Ever since that first volunteering job in Ghana it became my passion. Over the years I’ve gotten “distracted” with some other work, but somehow I always come back to this “architecture to help people” world. There is nothing more interesting that I could do and I feel extremely grateful to live in an environment that allows me to do it. Currently I work 28 hours a week in my paying job, and I devote the rest of the time to work in WEbuilding.”

Tell us about the first school in Damang, Ghana. Why did you decide to build it sustainably and how did you manage that?

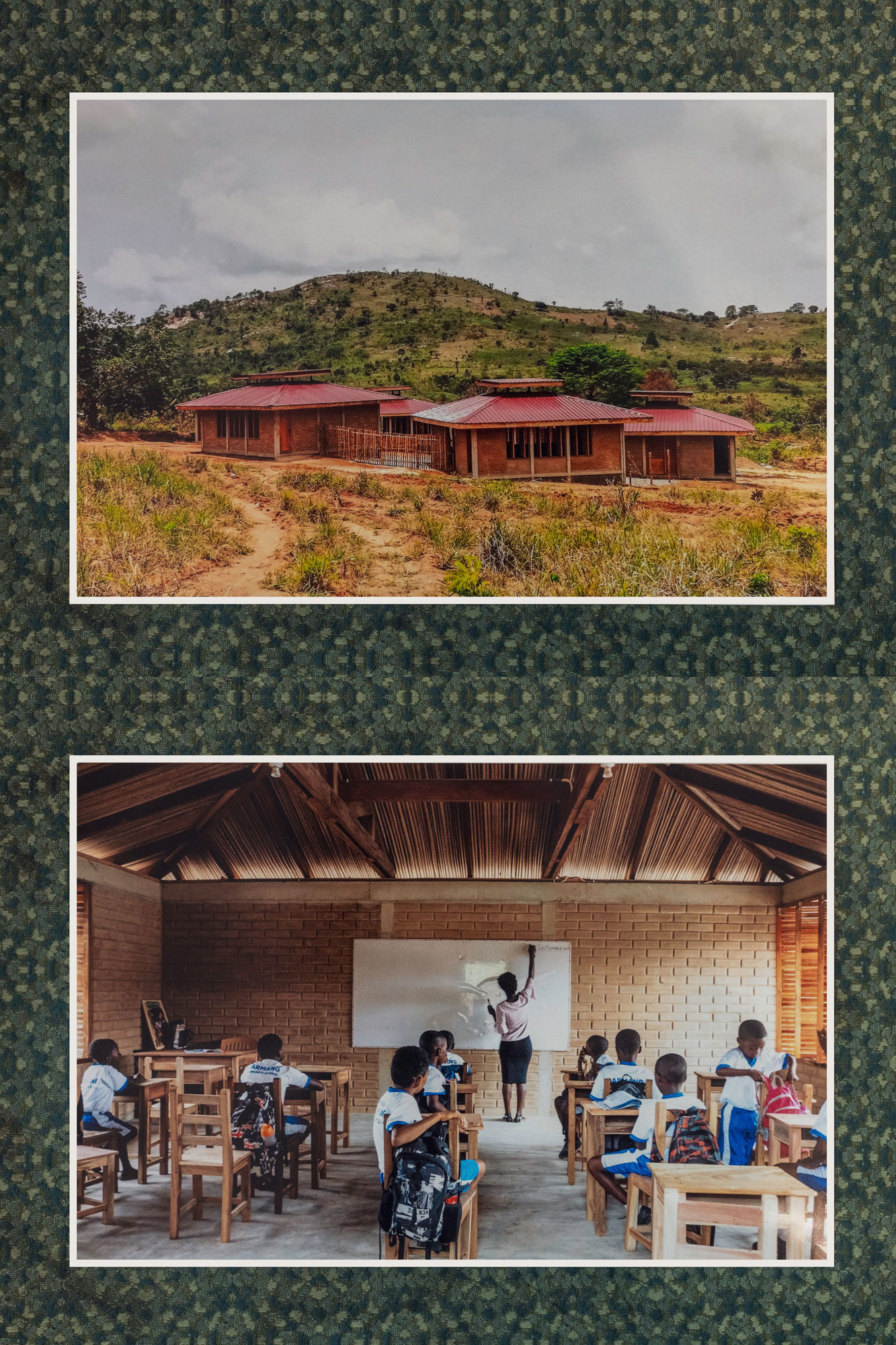

Laura: “Even though our primary goal is the social part, and that meant building a school for the children in Damang, there is always a decision on which materials and construction techniques to use. After a few months of living in Ghana, I realized local construction in the rural areas (which is made out of natural materials) doesn’t seem to be liked by the locals. We found that it’s a pity that a country where once foreign people came to learn about earth construction mostly turned its back on its own tradition. We thought we could use some more modern ideas and still be able to use natural and sustainable materials so that the maintenance is easier and the quality of the construction remains as high as it would be by using the “normal” materials.”

“We managed to build it, both sustainable and unsustainable parts, only with the support of a lot of people who volunteered their time and expertise to get it done. Although we had very experienced local contractors doing most of the construction work, in order to build everything exactly as we planned, we needed to do a lot of supervising of our own. While we were running things from a distance via Whatsapp and endless emails, our colleague Masa temporarily moved from Leipzig and spent six months in Damang overseeing the construction. Various other volunteers, mostly architects, spent around a month each on-site and helped out with whatever was needed. Most of us gathered for the school opening last September and it felt great to share that moment together.”

What does sustainability mean to you as architects and how do you apply the thinking to your process?

Ivan: “Sustainability is the buzzword nowadays, which is great, but in our field it should be taken with some moderation and adjusted to the project and the location. The most important thing is to find out which “sustainable” materials are available locally and then try to use that and not force something just for the sake of it.”

“We try to find some middle ground here and combine, as we did in the Damang project, using concrete, earth blocks and wood together. Sometimes being too sustainable could actually be unsustainable.”

Is building in a sustainable way harder than using other conventional methods? What makes it so?

Ivan: “Building sustainable requires a much higher level of knowledge from everyone in the design chain, especially the builders. It’s easy to say “let’s build this from rammed earth and old car tires” but if there is no one on site that actually has the know-how then it just doesn’t work. Taken all this into account, sustainable often means it is not cheap.”

“In our case we were lucky to meet Samuel, while doing our first “material scouting” trip back in 2015, and his fairly advanced compressed earth blocks that he does with a custom-made hydraulic machine. We immediately knew we had our main material and it is the one that gives the recognisable look to the classrooms.”

“These blocks are nothing new, they have been around in the 1950s in South America, but if there was not a “Samuel” doing them, one hour away from the school site, we would probably have to use something else.”

What was your biggest challenge in getting the first school built? How did you overcome this?

Laura: “It was a long process with a lot of challenges, but it always comes down to money. Getting the project funded was by far the hardest. With most other things it is in your power to accomplish the goals – be it from the whole administrative puzzle of registering a non-profit organisation in Germany, or carrying out the whole project management over WhatsApp.”

“But when it comes down to money applications, the only thing you can do is be stubborn and persistent and keep at it until you get a bit lucky. Took us around two years to finally manage it.”

School in Damang. Images © WEbuilding

Going through the process of building the school in Ghana, were there any surprises or things that happened that was totally unexpected? Even good surprises count here. If any.

Ivan: “Every day was a surprise! One day water well dries out, the other cement mixer brakes, then morning work starts, and we find a bunch of little kids’ footprints in our freshly poured concrete slab and so on. And apparently a 10 mm steel bar is called a 12 mm in Ghana. First we though we were cheated, then we realised it is a common practice of naming things.”

“The most pleasant surprise was to actually walk in those classrooms and realise we’ve all actually managed to pull it off. We were around only at the beginning of the construction, we followed it through photos and daily conversations. But to actually open the door and see that it turned out even better than we thought, was pretty amazing.”

What are you working on next and what are the biggest challenges you now face with this next project?

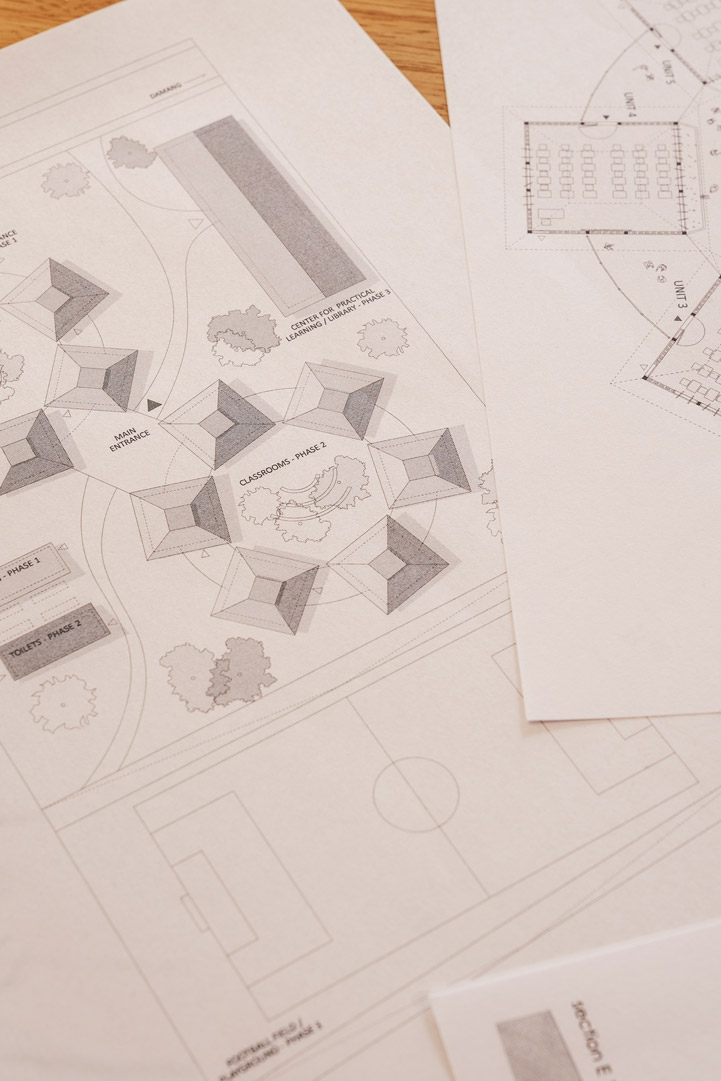

Laura: “We have a few ongoing projects. Another school in Koforidua, Ghana, where the projects are already done, and we’re applying for funding. A youth center in Douala, Cameroon, two potential school projects for indigenous communities in Colombia and the project that’s taking most of our time at the moment – Humbi Farm in Mozambique. The local NGO wants to make their existing children center more self sustainable by complementing it with a large permaculture farm, together with various buildings – greenhouse, workshops and basic volunteer accommodation.”

“Beside architecture projects, we are also trying to start a regular program for children workshops, and try to bring closer the culture of the countries we’re working in – currently Ghana, to the kids in Berlin.”

“The biggest challenge right now is trying to make our WEbuilding team bigger and incorporate more volunteers, since in order to do all those projects we definitely need more help.”

In your opinion, where is the biggest deficiency in architectural practices in the drive towards sustainability?

Ivan: “Sustainable architecture is mostly related to organic materials. There are big challenges that come from that. As an architect, designing buildings that use materials like earth or straw requires a lot of knowledge that you normally don’t get at a university. You have to investigate on your own, take various courses, do workshops, or if you don’t have that knowledge or time to learn it yourself, collaborate with people that know more than you. Once it comes down to construction, you actually need people on-site that know what they are doing and how to build with such materials. Or you need someone to teach everyone involved how to do it. All that should be taken into account even before starting the design.”

“And after all that, comes the hardest part, that doesn’t even have anything to do with architecture – maintenance! I would say maintaining public buildings is a big problem almost everywhere in the world – there is always a budget to build things, but rarely do you see budgets mentioning maintenance. So, now when your building is not completely made out of concrete that will stay there no matter what for generations, but rather out of earth or bamboo, you need local people with the knowledge and resources to take care of it year after year.”

How would you propose to solve this if at all solvable?

Ivan: “Little steps. Building more projects like we did, which use slightly more alternative methods of construction. But these sustainable alternatives shouldn’t be significantly more expensive, otherwise they will never catch on. Sustainable architecture here in Europe is a different thing, economically based on long term savings in heating and cooling. In tropical countries a different approach is needed.”

“What we see as crucial in this process is communication and open sharing of information with anyone interested in doing similar projects. Maybe even creating a “library” of some sorts – including advice, average prices, contacts etc. If we did some mistakes, there is no need for someone else to do them all over again. I suppose lots of architects do projects like these, once or twice in their career and then continue with their other work, and a lot of that knowledge and networking gets forgotten.

And finally, just for fun – Where are your favourite spots in Berlin for:

Breakfast or coffee: “Croissanterie in Pannierstrasse for breakfast or coffee at coffee corner in Kottbuserdamm.”

Spending a hot summers day: “In our rubber boat hanging out in the canal.”

Spending a cold winters day: “At home.”

Finding inspiration: “I’m very practical and I don’t look for inspiration.”

A night out with friends: “Späti inside Hasenheide.”

You can find out more about WEbuilding and how to get involved through their website. Or follow them on Instagram @webuilding to see what they are up to next.

Text & Photography © Barbara Cilliers

Energized by stories from creators?

Sign up to the newsletter for inspirational conversations with founders & creatives in their spaces.

Comments are closed.